Redux Essentials, Part 2: Redux Toolkit App Structure

- The structure of a typical React + Redux Toolkit app

- How to view state changes in the Redux DevTools Extension

Introduction

In Part 1: Redux Overview and Concepts, we looked at why Redux is useful, the terms and concepts used to describe different parts of Redux code, and how data flows through a Redux app.

Now, let's look at a real working example to see how these pieces fit together.

The Counter Example App

The sample project we'll look at is a small counter application that lets us add or subtract from a number as we click buttons. It may not be very exciting, but it shows all the important pieces of a React+Redux application in action.

The project has been created using a smaller version of the official Redux Toolkit template for Vite. Out of the box, it has already been configured with a standard Redux application structure, using Redux Toolkit to create the Redux store and logic, and React-Redux to connect together the Redux store and the React components.

Here's the live version of the project. You can play around with it by clicking the buttons in the app preview on the right, and browse through the source files on the left.

If you'd like to set up this project on your own computer, you can create a local copy with this command:

npx degit reduxjs/redux-templates/packages/rtk-app-structure-example my-app

You can also create a new project using the full Redux Toolkit template for Vite:

npx degit reduxjs/redux-templates/packages/vite-template-redux my-app

Using the Counter App

The counter app has already been set up to let us watch what happens inside as we use it.

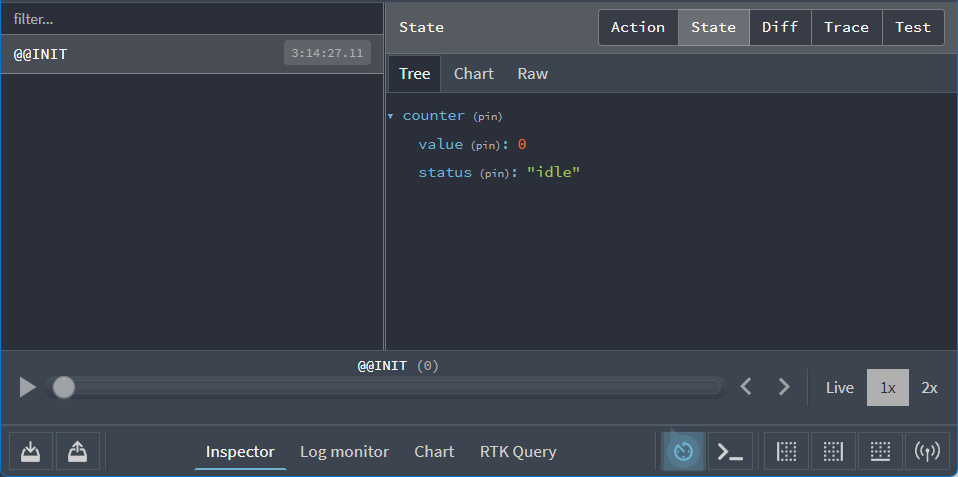

Open up your browser's DevTools. Then, choose the "Redux" tab in the DevTools, and click the "State" button in the upper-right toolbar. You should see something that looks like this:

On the right, we can see that our Redux store is starting off with an app state value that looks like this:

{

counter: {

value: 0

status: 'idle'

}

}

The DevTools will show us how the store state changes as we use the app.

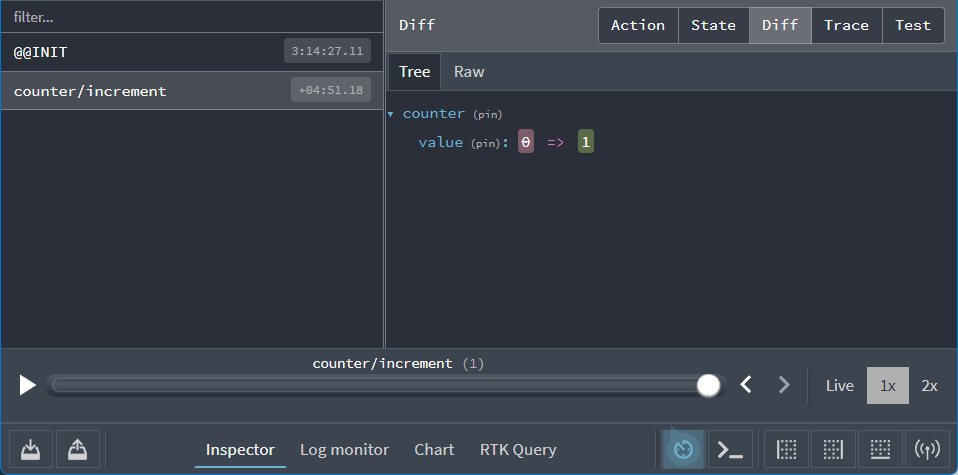

Let's play with the app first to see what it does. Click the "+" button in the app, then look at the "Diff" tab in the Redux DevTools:

We can see two important things here:

- When we clicked the "+" button, an action with a type of

"counter/increment"was dispatched to the store - When that action was dispatched, the

state.counter.valuefield changed from0to1

Now try these steps:

- Click the "+" button again. The displayed value should now be 2.

- Click the "-" button once. The displayed value should now be 1.

- Click the "Add Amount" button. The displayed value should now be 3.

- Change the number "2" in the textbox to a "3"

- Click the "Add Async" button. You should see a progress bar fill the button, and after a couple seconds, the displayed value should change to 6.

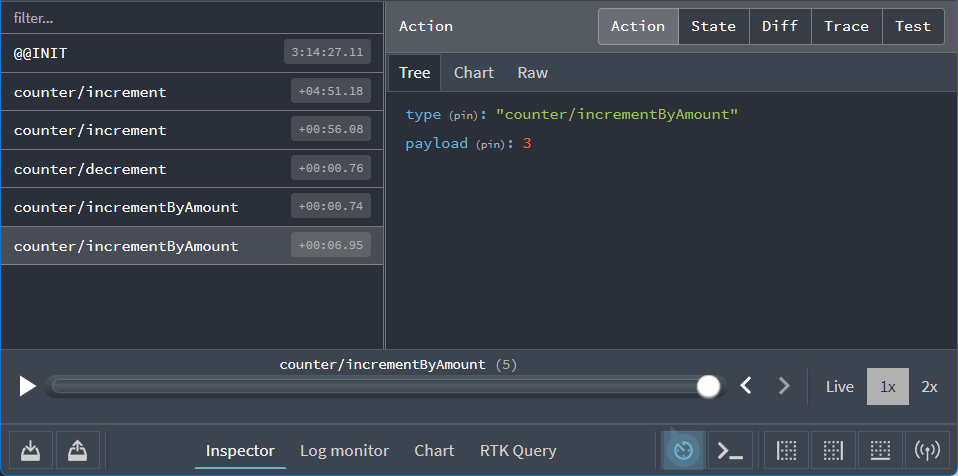

Go back to the Redux DevTools. You should see a total of five actions dispatched, one for each time we clicked a button . Now select the last "counter/incrementByAmount" entry from the list on the left, and click the "Action" tab on the right side:

We can see that this action object looked like this:

{

type: 'counter/incrementByAmount',

payload: 3

}

And if you click the "Diff" tab, you can see that the state.counter.value field changed from a 3 to a 6 in response to that action.

The ability to see what is happening inside of our app and how our state is changing over time is very powerful!

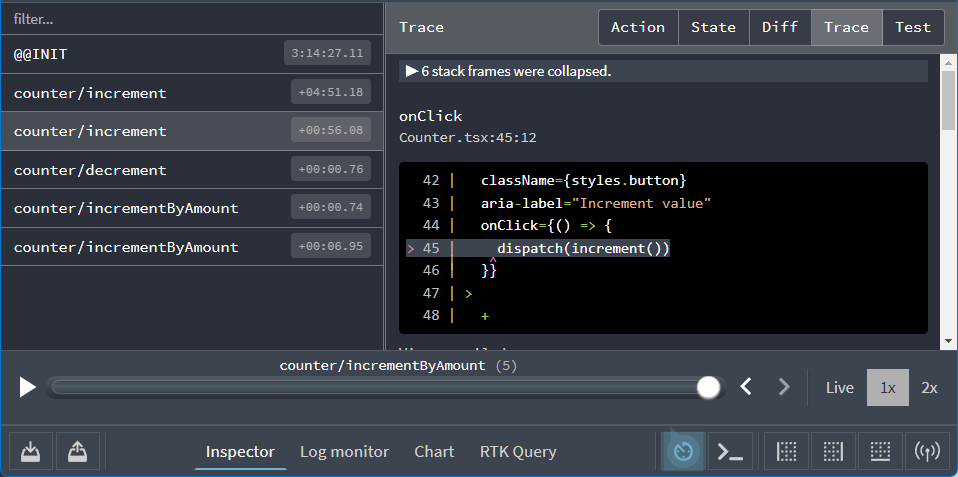

The DevTools have several more commands and options to help you debug your app. Try clicking the "Trace" tab in the upper right. You should see a JavaScript function stack trace in the panel, with several sections of source code showing the lines that were executing when the action reached the store. One line in particular should be highlighted: the line of code where we dispatched this action from the <Counter> component:

This makes it easier to trace what part of the code dispatched a specific action.

Application Contents

Now that you know what the app does, let's look at how it works.

Here are the key files that make up this application:

/srcmain.tsx: the starting point for the appApp.tsx: the top-level React component/appstore.ts: creates the Redux store instancehooks.ts: exports pre-typed React-Redux hooks

/features/counterCounter.tsx: a React component that shows the UI for the counter featurecounterSlice.ts: the Redux logic for the counter feature

Let's start by looking at how the Redux store is created.

Creating the Redux Store

Open up app/store.ts, which should look like this:

import type { Action, ThunkAction } from '@reduxjs/toolkit'

import { configureStore } from '@reduxjs/toolkit'

import counterReducer from '@/features/counter/counterSlice'

export const store = configureStore({

reducer: {

counter: counterReducer

}

})

// Infer the type of `store`

export type AppStore = typeof store

export type RootState = ReturnType<AppStore['getState']>

// Infer the `AppDispatch` type from the store itself

export type AppDispatch = AppStore['dispatch']

// Define a reusable type describing thunk functions

export type AppThunk<ThunkReturnType = void> = ThunkAction<

ThunkReturnType,

RootState,

unknown,

Action

>

The Redux store is created using the configureStore function from Redux Toolkit. configureStore requires that we pass in a reducer argument.

Our application might be made up of many different features, and each of those features might have its own reducer function. When we call configureStore, we can pass in all of the different reducers in an object. The key names in the object will define the keys in our final state value.

We have a file named features/counter/counterSlice.ts that exports a reducer function for the counter logic as the ESM "default" export. We can import that function into this file. Since it's a default export, we can give that variable any name we want when we import it into this file. In this case, we call it counterReducer here, and include it when we create the store. (Note that the import/export behavior here is standard ES Module syntax, and not specific to Redux.)

When we pass in an object like {counter: counterReducer}, that says that we want to have a state.counter section of our Redux state object, and that we want the counterReducer function to be in charge of deciding if and how to update the state.counter section whenever an action is dispatched.

Redux allows store setup to be customized with different kinds of plugins ("middleware" and "enhancers"). configureStore automatically adds several middleware to the store setup by default to provide a good developer experience, and also sets up the store so that the Redux DevTools Extension can inspect its contents.

For TypeScript usage, we also want to export some reusable types based on the Store, such as the RootState and AppDispatch types. We'll see how those get used later.

Redux Slices

A "slice" is a collection of Redux reducer logic and actions for a single feature in your app, typically defined together in a single file. The name comes from splitting up the root Redux state object into multiple "slices" of state.

For example, in a blogging app, our store setup might look like:

import { configureStore } from '@reduxjs/toolkit'

import usersReducer from '../features/users/usersSlice'

import postsReducer from '../features/posts/postsSlice'

import commentsReducer from '../features/comments/commentsSlice'

export const store = configureStore({

reducer: {

users: usersReducer,

posts: postsReducer,

comments: commentsReducer

}

})

In that example, state.users, state.posts, and state.comments are each a separate "slice" of the Redux state. Since usersReducer is responsible for updating the state.users slice, we refer to it as a "slice reducer" function.

Detailed Explanation: Reducers and State Structure

A Redux store needs to have a single "root reducer" function passed in when it's created. So if we have many different slice reducer functions, how do we get a single root reducer instead, and how does this define the contents of the Redux store state?

If we tried calling all of the slice reducers by hand, it might look like this:

function rootReducer(state = {}, action) {

return {

users: usersReducer(state.users, action),

posts: postsReducer(state.posts, action),

comments: commentsReducer(state.comments, action)

}

}

That calls each slice reducer individually, passes in the specific slice of the Redux state, and includes each return value in the final new Redux state object.

Redux has a function called combineReducers that does this for us automatically. It accepts an object full of slice reducers as its argument, and returns a function that calls each slice reducer whenever an action is dispatched. The result from each slice reducer are all combined together into a single object as the final result. We can do the same thing as the previous example using combineReducers:

const rootReducer = combineReducers({

users: usersReducer,

posts: postsReducer,

comments: commentsReducer

})

When we pass an object of slice reducers to configureStore, it passes those to combineReducers for us to generate the root reducer.

As we saw earlier, you can also pass a reducer function directly as the reducer argument:

const store = configureStore({

reducer: rootReducer

})

Creating Slice Reducers and Actions

Since we know that the counterReducer function is coming from features/counter/counterSlice.ts, let's see what's in that file, piece by piece.

import { createAsyncThunk, createSlice } from '@reduxjs/toolkit'

import type { PayloadAction } from '@reduxjs/toolkit'

// Define the TS type for the counter slice's state

export interface CounterState {

value: number

status: 'idle' | 'loading' | 'failed'

}

// Define the initial value for the slice state

const initialState: CounterState = {

value: 0,

status: 'idle'

}

// Slices contain Redux reducer logic for updating state, and

// generate actions that can be dispatched to trigger those updates.

export const counterSlice = createSlice({

name: 'counter',

initialState,

// The `reducers` field lets us define reducers and generate associated actions

reducers: {

increment: state => {

// Redux Toolkit allows us to write "mutating" logic in reducers. It

// doesn't actually mutate the state because it uses the Immer library,

// which detects changes to a "draft state" and produces a brand new

// immutable state based off those changes

state.value += 1

},

decrement: state => {

state.value -= 1

},

// Use the PayloadAction type to declare the contents of `action.payload`

incrementByAmount: (state, action: PayloadAction<number>) => {

state.value += action.payload

}

}

})

// Export the generated action creators for use in components

export const { increment, decrement, incrementByAmount } = counterSlice.actions

// Export the slice reducer for use in the store configuration

export default counterSlice.reducer

Earlier, we saw that clicking the different buttons in the UI dispatched three different Redux action types:

{type: "counter/increment"}{type: "counter/decrement"}{type: "counter/incrementByAmount"}

We know that actions are plain objects with a type field, the type field is always a string, and we typically have "action creator" functions that create and return the action objects. So where are those action objects, type strings, and action creators defined?

We could write those all by hand, every time. But, that would be tedious. Besides, what's really important in Redux is the reducer functions, and the logic they have for calculating new state.

Redux Toolkit has a function called createSlice, which takes care of the work of generating action type strings, action creator functions, and action objects. All you have to do is define a name for this slice, write an object that has some reducer functions in it, and it generates the corresponding action code automatically. The string from the name option is used as the first part of each action type, and the key name of each reducer function is used as the second part. So, the "counter" name + the "increment" reducer function generated an action type of {type: "counter/increment"}. (After all, why write this by hand if the computer can do it for us!)

In addition to the name field, createSlice needs us to pass in the initial state value for the reducers, so that there is a state the first time it gets called. In this case, we're providing an object with a value field that starts off at 0, and a status field that starts off with 'idle'.

We can see here that there are three reducer functions, and that corresponds to the three different action types that were dispatched by clicking the different buttons.

createSlice automatically generates action creators with the same names as the reducer functions we wrote. We can check that by calling one of them and seeing what it returns:

console.log(counterSlice.actions.increment())

// {type: "counter/increment"}

It also generates the slice reducer function that knows how to respond to all these action types:

const newState = counterSlice.reducer(

{ value: 10 },

counterSlice.actions.increment()

)

console.log(newState)

// {value: 11}

Rules of Reducers

We said earlier that reducers must always follow some special rules:

- They should only calculate the new state value based on the

stateandactionarguments - They are not allowed to modify the existing

state. Instead, they must make immutable updates, by copying the existingstateand making changes to the copied values. - They must be "pure" - they cannot do any asynchronous logic or other "side effects"

But why are these rules important? There are a few different reasons:

- One of the goals of Redux is to make your code predictable. When a function's output is only calculated from the input arguments, it's easier to understand how that code works, and to test it.

- On the other hand, if a function depends on variables outside itself, or behaves randomly, you never know what will happen when you run it.

- If a function modifies other values, including its arguments, that can change the way the application works unexpectedly. This can be a common source of bugs, such as "I updated my state, but now my UI isn't updating when it should!"

- Some of the Redux DevTools capabilities depend on having your reducers follow these rules correctly

The rule about "immutable updates" is particularly important, and worth talking about further.

Reducers and Immutable Updates

Earlier, we talked about "mutation" (modifying existing object/array values) and "immutability" (treating values as something that cannot be changed).

In Redux, our reducers are never allowed to mutate the original / current state values!

// ❌ Illegal - by default, this will mutate the state!

state.value = 123

There are several reasons why you must not mutate state in Redux:

- It causes bugs, such as the UI not updating properly to show the latest values

- It makes it harder to understand why and how the state has been updated

- It makes it harder to write tests

- It breaks the ability to use "time-travel debugging" correctly

- It goes against the intended spirit and usage patterns for Redux

So if we can't change the originals, how do we return an updated state?

Reducers can only make copies of the original values, and then they can mutate the copies.

// ✅ This is safe, because we made a copy

return {

...state,

value: 123

}

We already saw that we can write immutable updates by hand, by using JavaScript's array / object spread operators and other functions that return copies of the original values. However, if you're thinking that "writing immutable updates by hand this way looks hard to remember and do correctly"... yeah, you're right! :)

Writing immutable update logic by hand is hard, and accidentally mutating state in reducers is the single most common mistake Redux users make.

That's why Redux Toolkit's createSlice function lets you write immutable updates an easier way!

createSlice uses a library called Immer inside. Immer uses a special JS tool called a Proxy to wrap the data you provide, and lets you write code that "mutates" that wrapped data. But, Immer tracks all the changes you've tried to make, and then uses that list of changes to return a safely immutably updated value, as if you'd written all the immutable update logic by hand.

So, instead of this:

function handwrittenReducer(state, action) {

return {

...state,

first: {

...state.first,

second: {

...state.first.second,

[action.someId]: {

...state.first.second[action.someId],

fourth: action.someValue

}

}

}

}

}

You can write code that looks like this:

function reducerWithImmer(state, action) {

state.first.second[action.someId].fourth = action.someValue

}

That's a lot easier to read!

But, here's something very important to remember:

You can only write "mutating" logic in Redux Toolkit's createSlice and createReducer because they use Immer inside! If you write mutating logic in your code without Immer, it will mutate the state and cause bugs!

With that in mind, let's go back and look at the actual reducers from the counter slice.

export const counterSlice = createSlice({

name: 'counter',

initialState,

// The `reducers` field lets us define reducers and generate associated actions

reducers: {

increment: state => {

// Redux Toolkit allows us to write "mutating" logic in reducers. It

// doesn't actually mutate the state because it uses the Immer library,

// which detects changes to a "draft state" and produces a brand new

// immutable state based off those changes

state.value += 1

},

decrement: state => {

state.value -= 1

},

// Use the PayloadAction type to declare the contents of `action.payload`

incrementByAmount: (state, action: PayloadAction<number>) => {

state.value += action.payload

}

}

})

We can see that the increment reducer will always add 1 to state.value. Because Immer knows we've made changes to the draft state object, we don't have to actually return anything here. In the same way, the decrement reducer subtracts 1.

In both of those reducers, we don't actually need to have our code look at the action object. It will be passed in anyway, but since we don't need it, we can skip declaring action as a parameter for the reducers.

On the other hand, the incrementByAmount reducer does need to know something: how much it should be adding to the counter value. So, we declare the reducer as having both state and action arguments. In this case, we know that the amount we typed into the "amount" input is being put into the action.payload field, so we can add that to state.value.

If we're using TypeScript, we need to tell TS what the type of action.payload will be. The PayloadAction type declares that "this is an action object, where the type of action.payload is..." whatever type you supplied. In this case, we know that the UI has taken the numeric string that was typed into the "amount" textbox, converted it into a number, and is trying to dispatch the action with that value, so we'll declare that this is action: PayloadAction<number>.

For more information on immutability and writing immutable updates, see the "Immutable Update Patterns" docs page and The Complete Guide to Immutability in React and Redux.

For details on using Immer for "mutating" immutable updates, see the Immer docs and the "Writing Reducers with Immer" docs page.

Additional Redux Logic

The core of Redux is reducers, actions, and the store. There's a couple additional types of Redux functions that are commonly used as well.

Reading Data with Selectors

We can call store.getState() to get the entire current root state object, and access its fields like state.counter.value.

It's standard to write "selector" functions that do those state field lookups for us. In this case, counterSlice.ts exports two selector functions that can be reused:

// Selector functions allows us to select a value from the Redux root state.

// Selectors can also be defined inline in the `useSelector` call

// in a component, or inside the `createSlice.selectors` field.

export const selectCount = (state: RootState) => state.counter.value

export const selectStatus = (state: RootState) => state.counter.status

Selector functions are normally called with the entire Redux root state object as an argument. They can read out specific values from the root state, or do calculations and return new values.

Since we're using TypeScript, we also need to use the RootState type that was exported from store.ts to define the type of the state argument in each selector.

Note that you don't have to create separate selector functions for every field in every slice! (This particular example did, to show off the idea of writing selectors, but we only had two fields in counterSlice.ts anyway) Instead, find a balance in how many selectors you write.

We'll learn more about selector functions in Part 4: Using Redux Data, and look at how they can be optimized in Part 6: Performance

See Deriving Data with Selectors for a longer look at why and how to use selector functions.

Writing Async Logic with Thunks

So far, all the logic in our application has been synchronous. Actions are dispatched, the store runs the reducers and calculates the new state, and the dispatch function finishes. But, the JavaScript language has many ways to write code that is asynchronous, and our apps normally have async logic for things like fetching data from an API. We need a place to put that async logic in our Redux apps.

A thunk is a specific kind of Redux function that can contain asynchronous logic. Thunks are written using two functions:

- An inner thunk function, which gets

dispatchandgetStateas arguments - The outer creator function, which creates and returns the thunk function

The next function that's exported from counterSlice is an example of a thunk action creator:

// The function below is called a thunk, which can contain both sync and async logic

// that has access to both `dispatch` and `getState`. They can be dispatched like

// a regular action: `dispatch(incrementIfOdd(10))`.

// Here's an example of conditionally dispatching actions based on current state.

export const incrementIfOdd = (amount: number): AppThunk => {

return (dispatch, getState) => {

const currentValue = selectCount(getState())

if (currentValue % 2 === 1) {

dispatch(incrementByAmount(amount))

}

}

}

In this thunk, we use getState() to get the store's current root state value, and dispatch() to dispatch another action. We could easily put async logic here as well, such as a setTimeout or an await.

We can use them the same way we use a typical Redux action creator:

store.dispatch(incrementIfOdd(6))

Using thunks requires that the redux-thunk middleware (a type of plugin for Redux) be added to the Redux store when it's created. Fortunately, Redux Toolkit's configureStore function already sets that up for us automatically, so we can go ahead and use thunks here.

When writing thunks, we need to make sure the dispatch and getState methods are typed correctly. We could define the thunk function as (dispatch: AppDispatch, getState: () => RootState), but it's standard to define a reusable AppThunk type for that in the store file.

When you need to make HTTP calls to fetch data from the server, you can put that call in a thunk. Here's an example that's written a bit longer, so you can see how it's defined:

// the outside "thunk creator" function

const fetchUserById = (userId: string): AppThunk => {

// the inside "thunk function"

return async (dispatch, getState) => {

try {

dispatch(userPending())

// make an async call in the thunk

const user = await userAPI.fetchById(userId)

// dispatch an action when we get the response back

dispatch(userLoaded(user))

} catch (err) {

// If something went wrong, handle it here

}

}

}

Redux Toolkit includes a createAsyncThunk method that does all of the dispatching work for you. The next function in counterSlice.ts is an async thunk that makes a mock API request with a counter value. When we dispatch this thunk, it will dispatch a pending action before making the request, and either a fulfilled or rejected action after the async logic is done.

// Thunks are commonly used for async logic like fetching data.

// The `createAsyncThunk` method is used to generate thunks that

// dispatch pending/fulfilled/rejected actions based on a promise.

// In this example, we make a mock async request and return the result.

// The `createSlice.extraReducers` field can handle these actions

// and update the state with the results.

export const incrementAsync = createAsyncThunk(

'counter/fetchCount',

async (amount: number) => {

const response = await fetchCount(amount)

// The value we return becomes the `fulfilled` action payload

return response.data

}

)

When you use createAsyncThunk, you handle its actions in createSlice.extraReducers. In this case, we handle all three action types, update the status field, and also update the value:

export const counterSlice = createSlice({

name: 'counter',

initialState,

reducers: {

// omit reducers

},

// The `extraReducers` field lets the slice handle actions defined elsewhere,

// including actions generated by createAsyncThunk or in other slices.

extraReducers: builder => {

builder

// Handle the action types defined by the `incrementAsync` thunk defined below.

// This lets the slice reducer update the state with request status and results.

.addCase(incrementAsync.pending, state => {

state.status = 'loading'

})

.addCase(incrementAsync.fulfilled, (state, action) => {

state.status = 'idle'

state.value += action.payload

})

.addCase(incrementAsync.rejected, state => {

state.status = 'failed'

})

}

})

If you're curious why we use thunks for async logic, see this deeper explanation:

Detailed Explanation: Thunks and Async Logic

We know that we're not allowed to put any kind of async logic in reducers. But, that logic has to live somewhere.

If we had access to the Redux store, we could write some async code and call store.dispatch() when we're done:

const store = configureStore({ reducer: counterReducer })

setTimeout(() => {

store.dispatch(increment())

}, 250)

But, in a real Redux app, we're not allowed to import the store into other files, especially in our React components, because it makes that code harder to test and reuse.

In addition, we often need to write some async logic that we know will be used with some store, eventually, but we don't know which store.

The Redux store can be extended with "middleware", which are a kind of add-on or plugin that can add extra abilities. The most common reason to use middleware is to let you write code that can have async logic, but still talk to the store at the same time. They can also modify the store so that we can call dispatch() and pass in values that are not plain action objects, like functions or Promises.

The Redux Thunk middleware modifies the store to let you pass functions into dispatch. In fact, it's short enough we can paste it here:

const thunkMiddleware =

({ dispatch, getState }) =>

next =>

action => {

if (typeof action === 'function') {

return action(dispatch, getState)

}

return next(action)

}

It looks to see if the "action" that was passed into dispatch is actually a function instead of a plain action object. If it's actually a function, it calls the function, and returns the result. Otherwise, since this must be an action object, it passes the action forward to the store.

This gives us a way to write whatever sync or async code we want, while still having access to dispatch and getState.

We'll see thunks being used in Part 5: Async Logic and Data Fetching

See the Redux Thunk docs, the post What the heck is a thunk? and the Redux FAQ entry on "why do we use middleware for async?" for more information.

The React Counter Component

Earlier, we saw what a standalone React <Counter> component looks like. Our React+Redux app has a similar <Counter> component, but it does a few things differently.

We'll start by looking at the Counter.tsx component file:

import { useState } from 'react'

// Use pre-typed versions of the React-Redux

// `useDispatch` and `useSelector` hooks

import { useAppDispatch, useAppSelector } from '@/app/hooks'

import {

decrement,

increment,

incrementAsync,

incrementByAmount,

incrementIfOdd,

selectCount,

selectStatus

} from './counterSlice'

import styles from './Counter.module.css'

export function Counter() {

const dispatch = useAppDispatch()

const count = useAppSelector(selectCount)

const status = useAppSelector(selectStatus)

const [incrementAmount, setIncrementAmount] = useState('2')

const incrementValue = Number(incrementAmount) || 0

return (

<div>

<div className={styles.row}>

<button

className={styles.button}

aria-label="Decrement value"

onClick={() => {

dispatch(decrement())

}}

>

-

</button>

<span aria-label="Count" className={styles.value}>

{count}

</span>

<button

className={styles.button}

aria-label="Increment value"

onClick={() => {

dispatch(increment())

}}

>

+

</button>

{/* omit additional rendering output here */}

</div>

</div>

)

}

Like with the earlier plain React example, we have a function component called Counter, that stores some data in a useState hook.

However, in our component, it doesn't look like we're storing the actual current counter value as state. There is a variable called count, but it's not coming from a useState hook.

While React includes several built-in hooks like useState and useEffect, other libraries can create their own custom hooks that use React's hooks to build custom logic.

The React-Redux library has a set of custom hooks that allow your React component to interact with a Redux store.

Reading Data with useSelector

First, the useSelector hook lets our component extract whatever pieces of data it needs from the Redux store state.

Earlier, we saw that we can write "selector" functions, which take state as an argument and return some part of the state value. In particular, our counterSlice.ts file is exporting selectCount and selectStatus

If we had access to a Redux store, we could retrieve the current counter value as:

const count = selectCount(store.getState())

console.log(count)

// 0

Our components can't talk to the Redux store directly, because we're not allowed to import it into component files. But, useSelector takes care of talking to the Redux store behind the scenes for us. If we pass in a selector function, it calls someSelector(store.getState()) for us, and returns the result.

So, we can get the current store counter value by doing:

const count = useSelector(selectCount)

We don't have to only use selectors that have already been exported, either. For example, we could write a selector function as an inline argument to useSelector:

const countPlusTwo = useSelector((state: RootState) => state.counter.value + 2)

Any time an action has been dispatched and the Redux store has been updated, useSelector will re-run our selector function. If the selector returns a different value than last time, useSelector will make sure our component re-renders with the new value.

Dispatching Actions with useDispatch

Similarly, we know that if we had access to a Redux store, we could dispatch actions using action creators, like store.dispatch(increment()). Since we don't have access to the store itself, we need some way to have access to just the dispatch method.

The useDispatch hook does that for us, and gives us the actual dispatch method from the Redux store:

const dispatch = useDispatch()

From there, we can dispatch actions when the user does something like clicking on a button:

<button

className={styles.button}

aria-label="Increment value"

onClick={() => {

dispatch(increment())

}}

>

+

</button>

Defining Pre-Typed React-Redux Hooks

By default the useSelector hook needs you to declare (state: RootState) for every selector function. We can create pre-typed versions of the useSelector and useDispatch hooks so that we don't have to keep repeating the : RootState part every time.

import { useDispatch, useSelector } from 'react-redux'

import type { AppDispatch, RootState } from './store'

// Use throughout your app instead of plain `useDispatch` and `useSelector`

export const useAppDispatch = useDispatch.withTypes<AppDispatch>()

export const useAppSelector = useSelector.withTypes<RootState>()

Then, we can import the useAppSelector and useAppDispatch hooks into our own components and use them instead of the original versions.

Component State and Forms

By now you might be wondering, "Do I always have to put all my app's state into the Redux store?"

The answer is NO. Global state that is needed across the app should go in the Redux store. State that's only needed in one place should be kept in component state.

In this example, we have an input textbox where the user can type in the next number to be added to the counter:

const [incrementAmount, setIncrementAmount] = useState('2')

const incrementValue = Number(incrementAmount) || 0

// later

return (

<div className={styles.row}>

<input

className={styles.textbox}

aria-label="Set increment amount"

value={incrementAmount}

onChange={e => setIncrementAmount(e.target.value)}

/>

<button

className={styles.button}

onClick={() => dispatch(incrementByAmount(incrementValue))}

>

Add Amount

</button>

<button

className={styles.asyncButton}

onClick={() => dispatch(incrementAsync(incrementValue))}

>

Add Async

</button>

</div>

)

We could keep the current number string in the Redux store, by dispatching an action in the input's onChange handler and keeping it in our reducer. But, that doesn't give us any benefit. The only place that text string is used is here, in the <Counter> component. (Sure, there's only one other component in this example: <App>. But even if we had a larger application with many components, only <Counter> cares about this input value.)

So, it makes sense to keep that value in a useState hook here in the <Counter> component.

Similarly, if we had a boolean flag called isDropdownOpen, no other components in the app would care about that - it should really stay local to this component.

In a React + Redux app, your global state should go in the Redux store, and your local state should stay in React components.

If you're not sure where to put something, here are some common rules of thumb for determining what kind of data should be put into Redux:

- Do other parts of the application care about this data?

- Do you need to be able to create further derived data based on this original data?

- Is the same data being used to drive multiple components?

- Is there value to you in being able to restore this state to a given point in time (ie, time travel debugging)?

- Do you want to cache the data (ie, use what's in state if it's already there instead of re-requesting it)?

- Do you want to keep this data consistent while hot-reloading UI components (which may lose their internal state when swapped)?

This is also a good example of how to think about forms in Redux in general. Most form state probably shouldn't be kept in Redux. Instead, keep the data in your form components as you're editing it, and then dispatch Redux actions to update the store when the user is done.

One other thing to note before we move on: remember that incrementAsync thunk from counterSlice.ts? We're using it here in this component. Notice that we use it the same way we dispatch the other normal action creators. This component doesn't care whether we're dispatching a normal action or starting some async logic. It only knows that when you click that button, it dispatches something.

Providing the Store

We've seen that our components can use the useSelector and useDispatch hooks to talk to the Redux store. But, since we didn't import the store, how do those hooks know what Redux store to talk to?

Now that we've seen all the different pieces of this application, it's time to circle back to the starting point of this application and see how the last pieces of the puzzle fit together.

import React from 'react'

import { createRoot } from 'react-dom/client'

import { Provider } from 'react-redux'

import App from './App'

import { store } from './app/store'

import './index.css'

const container = document.getElementById('root')!

const root = createRoot(container)

root.render(

<React.StrictMode>

<Provider store={store}>

<App />

</Provider>

</React.StrictMode>

)

We always have to call root.render(<App />) to tell React to start rendering our root <App> component. In order for our hooks like useSelector to work right, we need to use a component called <Provider> to pass down the Redux store behind the scenes so they can access it.

We already created our store in app/store.ts, so we can import it here. Then, we put our <Provider> component around the whole <App>, and pass in the store: <Provider store={store}>.

Now, any React components that call useSelector or useDispatch will be talking to the Redux store we gave to the <Provider>.

What You've Learned

Even though the counter example app is pretty small, it showed all the key pieces of a React + Redux app working together. Here's what we covered:

- We can create a Redux store using the Redux Toolkit

configureStoreAPIconfigureStoreaccepts areducerfunction as a named argumentconfigureStoreautomatically sets up the store with good default settings

- Redux logic is typically organized into files called "slices"

- A "slice" contains the reducer logic and actions related to a specific feature / section of the Redux state

- Redux Toolkit's

createSliceAPI generates action creators and action types for each individual reducer function you provide

- Redux reducers must follow specific rules

- Should only calculate a new state value based on the

stateandactionarguments - Must make immutable updates by copying the existing state

- Cannot contain any asynchronous logic or other "side effects"

- Redux Toolkit's

createSliceAPI uses Immer to allow "mutating" immutable updates

- Should only calculate a new state value based on the

- Reading values from the state is done with functions called "selectors"

- Selectors accept

(state: RootState)as their argument and either return a value from the state, or derive a new value - Selectors can be written in slice files, or inline in the

useSelectorhook

- Selectors accept

- Async logic is typically written in special functions called "thunks"

- Thunks receive

dispatchandgetStateas arguments - Redux Toolkit enables the

redux-thunkmiddleware by default

- Thunks receive

- React-Redux allows React components to interact with a Redux store

- Wrapping the app with

<Provider store={store}>enables all components to use the store - The

useSelectorhook lets React components read values from the Redux store - The

useDispatchhook lets components dispatch actions - For TS usage, we create pre-typed

useAppSelectoranduseAppDispatchhooks - Global state should go in the Redux store, local state should stay in React components

- Wrapping the app with

What's Next?

Now that you've seen all the pieces of a Redux app in action, it's time to write your own! For the rest of this tutorial, you'll be building a larger example app that uses Redux. Along the way, we'll cover all the key ideas you need to know to use Redux the right way.

Continue on to Part 3: Basic Redux Data Flow to get started building the example app.